This post is part of a series focused on exploring DVS 2020 survey data to understand more about tool usage in data vis. See other posts in the series using the ToolsVis tag.

In the last post, I tried taking a step back to get a new perspective on the reduced branches visualization I’d been working on in the post before. Sometimes you just run into a stubborn problem, and it’s more productive to look for a way around or spend some time wandering in the wilderness rather than banging up against a massive boulder in the way.

I initially abandoned the reduced branches vis because I realized that I was reinventing the wheel with the Excel analysis, and had spent a week of project time basically replicating manually what I’d already done in R. (Surprise! Gotta love redoing work because you didn’t recognize the problem from a different angle.) But there was also something interesting here, and I knew that it was helping me to see the same data in a different way, even if it wasn’t doing quite what I wanted yet.

In my experience, when I get stuck on something like this it’s usually because I’m trying to take too many steps at once, and I’m missing some crucial piece in the middle that helps to make the rest make sense. If I can’t make the leap, I don’t worry about it; I just go back a few steps and start to work my way forward from the beginning to see if I can find the missing link. A little perspective never hurts, and I often find things that I didn’t know I needed along the way.

I stepped back to the pairwise analysis and built those visualizations out instead, to solidify my understanding of what was happening with the data in those more limited spaces. As I was working on the pairwise analysis, the reduced branches approach kept coming up again and again, confirming my sense that there’s something in here to see, if I can just figure out how to solve for it. I do a lot of this in exploratory work: sometimes I spend weeks pacing around the perimeter of a problem, trying to understand its shape and figure out a way in. I also spend a lot of time observing myself and noticing what I’m drawn to, and which ideas I just can’t leave alone. The whole time I was on that little detour, a part of me knew that I was on the right path in the first place, and that I was probably going to need to tackle that boulder eventually.

After taking a bit of a breather with my little walkabout in pairwise analysis, I decided to come back around to the reduced branches vis, and to start feeling my way forward again from there.

When I finished thinking through the correlation vis in the last post, I could feel that I was on the edge of making a connection that mattered. If the correlation map is a microscope that zooms in on one branch at a time using filters, the branches vis is the wide angle lens that I was grasping for but couldn’t quite get a hold on…yet.

I spent another week or two paying attention to that thought, feeling it hover in my peripheral vision, just outside of reach. If I turned my head to look at it directly, it melted away, but I could feel my brain crunching on the problem, consolidating and thinking it through. This can be a pretty absorbing pursuit sometimes, which seems odd when you consider that I don’t actually know what I’m thinking at this point in the process. I feel like I’m stepping back and letting my brain crunch on the problem without me, sometimes with more or less visibility into what’s going on inside. It’s usually not productive to try to interfere; I just let things run without meddling, and put the more verbal part of me to work playing scribe. My brain just sort of goes off and does its thing, and I sit and wait for it to come back with something useful.

This kind of absorption in a problem can lead to strange behaviors: there was a one morning in this period of the project where my husband was startled to come into the kitchen and find me just standing there, leaning over with my forehead resting on the counter, waiting for a kettle of tea to boil. I assured him that yes, thank you, I am fine…just thinking, we laughed a bit at the occasional oddness of being me, and then I went back to crunching away on the problem, waiting and watching for whatever insight was trying to come through. A problem that seems intractable in one session is suddenly completely clear in the next, and if I humor it I often wake up with my brain so full of thoughts and answers that I can’t keep up. As long as there is no deadline, I just let my mind go where it wants, and pay attention to what those pathways tell me about the shape of the problem itself.

When I get into this state, it’s my job to simply observe what’s going on and look for clues. These are never clear, and they usually don’t make any sense. They’re sort of like Zen koans floating up from the depths to puzzle me. One clue was that this problem felt like a series of strings going through a loom. They’re all in parallel, but they get grouped differently at every stage. That was important. The groupings are also changing, based on my selections, so that the same string might be getting grouped in multiple ways, and a different one each time. You want to be able to follow an individual string, but you need to pay attention to the groups as well. Each branching point is a step in the analysis, but the important thing that I learned from the parallel y plot was that the strings needed to be able to skip a step. What does that even mean? I had no idea.

Another thing that helps in this stage is writing things out. Writing forces things to be at least somewhat linear, and it creates a series of thoughts that you can edit and rearrange. When I’m having trouble assembling the pieces in my head, I just put them on paper where I can see them all at once. When things are written down, I no longer have to remember them. If I can put the whole picture down for a while, it frees up space so that I can focus on the individual details and understand how they work. I don’t worry about editing or organizing at this stage; I simply sit down and take dictation, catching as many thoughts as I can from the torrent running through my brain. I never catch them all, and sometimes I lose something that feels really important before it’s complete. That’s ok; I just let it flow and trust that things will come back. You can always edit it later. You don’t have to publish your stream of consciousness.

Once I’ve freed up some space to think, I can puzzle at all of the individual pieces and work on the tiny connecting details as much as I want without losing sight of the whole. I need to be deep, deep into a problem to make progress and feed my brain in figuring out what to do with it, but it’s also important to get some distance and step back. For me, writing is a good way to do that. Post-it boards, brainstorming sessions, and rough, ugly sketches are other approaches that can also work, depending on the task. In this case, I took a few weeks off to draft a bunch of blog posts that would turn into a these posts and eventually a series of Nightingale articles (and possibly a section of a book draft that I’m working on), and to ponder the bigger questions about what I was really doing and what I was trying to achieve.

It’s important to realize that I’m not procrastinating or wasting time here. I am still making progress, albeit slowly, toward my goal. If I let myself get too distracted or if I forget to come back and engage with the data problem directly, then this additional effort will be wasted. But if I can keep my brain engaged with the structure of the problem, then doing something else is often the most productive way through a major block. It’s like watching a wild animal: you need to pay attention without looking, and wait for it to get comfortable enough to show up.

In this case, writing about the process and the different visualizations helped me to see that the core problem was that the “threads” in my parallel y plot can skip a node without participating, and I didn’t want that to artificially turn them into another branch. The metaphor of threads on a loom was a helpful one for me, because it helped me see that I was essentially gathering the material along those threads. So what would it mean to stretch that fabric back out? Here’s an example of some of that stream-of-consciousness writing. Notice that I’m focusing on describing the problem, and using that information to guess at the “what” that’s needed for this particular data set.

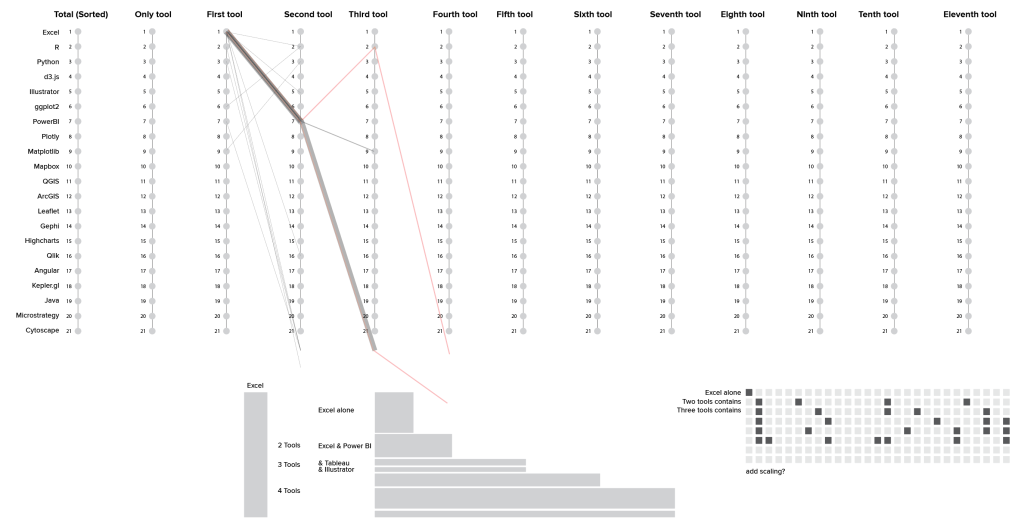

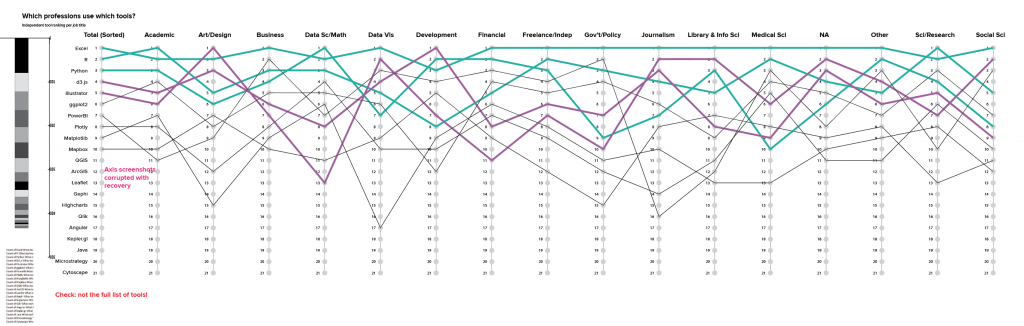

First, I think it means taking a step back toward the non-reduced list, where every tool has a column in a particular order. That sets the sequence, and the spacing of threads. I don’t want that sequence to dominate in the final product, but for right now the structure is useful to help me make sense of the chaos. It’s also very important that the final vis shows the gathered material, not the structure. I want to be able to pick up a group of threads independently, based on their shared path. At that point, I want the structure to fade so that all I see is the grouping instead. Like playing chords on a piano, the combination of keys you hit is just a subset of the individual notes. The keys might be in an order to help you find the tones, but the tune you play on top of that structure is another layer. That’s another important clue: this is about temporary states selected from a single structure, not different structures or a lack of order. Coming back to data vis world for a second, that probably means interactions on top of a structured vis, rather than a completely unstructured network or another amorphous form.

So then, what is the structure? I think the problem with the multiple y vis is that it focuses too much on the steps (the tie points where the thread intersects the fabric), and not enough on the gathers that those steps cause. I need to stretch this back out into the flat fabric, which is essentially the non-reduced Excel sheet, with all of the empty spaces put back in. That’s the structure, but the music is the gather, and it pulls the fabric together in different ways, depending on which threads you use. This tells me that the parallel axes should be the tools. In the first parallel y that I created, the axes were the job titles.

In the second, they were the sequence of tools listed in each branch.

These are both important qualities, and need to remain core aspects of the final visualization, but I’m projecting the branches onto the wrong variable space. Ok. So which space should it be, instead?

I think the axes need to be the individual tools, and the branches should be the individual lines. This takes me all the way back to the structure of my Excel sheet, like I’m trying to visualize the whole thing at once. That’s the structure underneath, the fabric that holds all of these strings together…

I certainly don’t have a clear picture of where I’m going at the end of this exercise, but I have a better sense of which things are important (or, at least a sense of which things feel important at the time…we’ll see later that I was wrong about a key feature here). I’m also not afraid to mix metaphors, and to use any description that helps me to capture a piece of what the final thing should be. Those contradictions are part of it. I know that I can only see fragments right now, but every fragment is a clue. Like the blind men describing an elephant, each perspective holds an important piece of the puzzle. The real challenge will be figuring out which ones are accurate or valuable, and how they all fit together.

In this instance, I found that I kept coming back to the question of branches, and whether I need aggregated or individual items to do the analysis. I want to see branching without an implied sequence, which reinforces the notion of clusters being the kind of analysis I need. I see multiple views from the same data, and I want the ability to switch between them. I’ve built at least 3 different kinds of filter structures: things that help me to focus in with a microscope on a single branch and follow it along its length. But each time, I find that I want to step back and look at the whole thing instead. The microscope is interesting, but it’s that panoramic perspective that I want first, and then again during the microscopic analysis to provide context.

Each of these things is telling me something about the “what” for the final visualization, and helping me to build a picture of what the solution could be. I don’t care about the form yet. In fact, I try to avoid thinking about it at all, except insofar as it helps me to describe the features that I need; that will have to be optimized along with the data and the story later. For now, I am looking for the structure and the capabilities that support the visual story that I want to tell.

- Interactive, probably with some mechanism for drill-down or facets/segmentation

- Sequence of increasing resolution, as a user focuses in on the group that matters most to them

- Possibly some descriptive counts to give context, but those aren’t the core story

- Multiple views and flexible controls that allow the user to switch between them

- Transitions/tracing to help them follow the change

- Complex image, viewed at multiple levels of resolution; different features emerge at each one

- Highly fragmented data; image is likely to be composed of individual pixels, not aggregated into discrete visual entities.

That last point makes me wonder about generative art, but I’m getting too far ahead of myself there. It’s enough that the point is noted, and we’re going to avoid going down that particular rabbit hole for now. I can’t explain exactly how I decide which rabbit holes are worth pursuing and which aren’t. My general rule is that things have to feel like they’re pulling together rather than flying apart, though what that means varies from project to project and from day to day. For now, generative art feels like it’s heading off in a completely new direction, so I’ll leave it to sit for a while and pursue something that feels closer to the core problem instead. To me, learning to trust that sense of direction is one of the most important parts of gaining experience: I get a lot farther when I lean in and say yes to my crazy, random ideas than when I fight them.

2 thoughts on “Tackling the Boulder”