My thesis seminar section is beginning to plan for the class exhibition in April. My thesis project is web-based, so the challenge for me will be to turn a detailed exploratory site into something that users can engage with in a few minutes in physical space.

The thesis project is about soil: as an ecosystem, and how it relates to human concerns. Partly, my hope is that people will see that soil is more than just dirt, and that the health of the soil is critical to human food production as well. The story includes population growth, increasing food demands, and soil depletion worldwide, but I don’t want fear of scarcity to be the primary message of the project. Instead, I hope to convey the many issues that intersect in this one topic, and to reflect the diversity of perspectives and cognitive frames that make easy answers difficult to find.

Making such a subtle argument requires prolonged user engagement with the topic, and there isn’t time for that at the exhibition. So I started by stepping back to identify the most important things I hope people will come away with. First, soil is interesting. It’s not something that most people think much about, and I think that understanding the complexity of the soil ecosystem will inspire the wonder that I want to lead this conversation.

Second, soil is important. The impacts of soil health stretch far beyond any one square meter of earth that is depleted or doing well. 95% of human food comes from the soil, it supports 23% of the world’s species, and as the second-largest land-based carbon storage system (behind coal, oil and gas reserves), soil has important implications for climate change as well.

Third, soil is under threat. Human impacts have led to widespread depletion of soils across the globe. Improving farming practices to reduce erosion and careful consideration of land use and urban development are key drivers in creating change.

That’s still a lot to get across in 5 minutes, so I went one step farther and asked myself which of these things I would say if I could only say one. I decided to emphasize the first, because I think creating a sense of wonder and curiosity is the most important thing that designers can do for science. Once a person has become curious, they can find additional information on their own, and they will be more motivated to do it. Without curiosity or interest, all of the facts and statistics in the world won’t do much to change someone’s mind.

So, how to convey the importance of soil in a visual way, while also taking advantage of physical space? I started thinking about the relationship between soil and plants, as the real bridge to human concerns. Part of the difficulty of this topic is that soil is underground and unseen. How could I make these complicated relationships visible?

It’s difficult to show the microbial side of these relationships without advanced microscopes, but just looking at the plant root system opens up an opportunity to start the conversation about what happens underground. I read about scientists using transparent soil in Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees, which I read over break. The science-grade substitute is pretty involved, so I’d have to get access to a lab and some pretty advanced equipment (as well as permission to order from chemical supply companies as an individual rather than an institution) for that. I did start looking at university websites in the Boston area for labs that might be willing to collaborate, but after further poking around online, I found a company that makes a gelatin-based soil substitute that’s supposed to work with houseplants. That’s a much simpler proposition, so I figured I’d start there for now.

I also wanted to show the contrast between a soil substitute and a soil ecosystem. It is possible to grow plants without soil, just as it’s possible to keep people alive on Ensure. But plants rely on the microorganisms in their rhizosphere (the soil surrounding their root system) just as much as humans depend on the bacteria in our guts and on our skin. In both cases, intricate microbial communities are critical parts of a healthy organism. You can grow “germ free” mice without a microbiome, but they end up with compromised immune systems and chronic disease.

To emphasize this contrast, I decided to make a side-by-side comparison of plants growing in soil substitute and plants growing in soil. I still wanted the roots to be visible, though, so I started thinking about how to make roots visible inside a pot. In the end, I settled on using a very thin glass container, so that the plant roots would be likely to press up against the edges of the glass. Of course, that’s not a standard format for plant growth, so I had to be a bit more creative.

I took a trip to AC Moore, and found these “floating frames” with two panes of glass and a plastic separator between them.

A stop at Home Depot provided some marine sealant to make the edges watertight, and after cutting out a portion of the top section of the plastic, I caulked up a glass and plastic sandwich.

Branden took the frame to work, where he has access to a milling machine and was able to cut away a portion of the frame with a drill.

To mimic the structure of a real soil, I started out with a layer of small rocks and rock chips, and then a thin layer of sand. On top of this, I poured dried out soil from my back garden, to fill the rest of the frame. It was interesting to see just how much air was left between particles when I was done; that’s critical for helping the plant to breathe.

I have a small fig tree that has outgrown its pot and needs to be cut back, and it has been desperately sending out root nubs all along its stems in an effort to find more dirt. I wrapped two of these stems in a damp paper towel and surrounded them in plastic a couple of weeks ago, and have kept the paper towel damp since then to encourage root growth.

Today, I took a deep breath and chopped off one of the branches. I inserted the cut end of the stem into the soil, and used a bamboo skewer to make good contact. Then, I added water.

It was interesting to watch how the water absorbed into the dry soil. It followed the plant stem down to the bottom, and then absorbed out from there. I wonder if this happens all the time in nature? Does the top of the tree act like a funnel to make sure that water gets directed to its roots? Not sure, but I thought that watching the plume of water develop was interesting.

Once the plant was watered and placed in its frame, I wrapped the whole thing in aluminum foil to protect it from the light (plant roots don’t like to be exposed to light, and I don’t want them to avoid the surface of the glass while growing). I also pulled off about half of the leaves from the stem; I hate to do that part, but the leaves require a lot of water and it will take a while before the root nubs will be able to support that many leaves, so cutting most of them off helps to keep the plant from going into shock. After a rather traumatic morning, the cutting is now sitting in its new frame under the grow light at my desk.

While I was setting up the frame version, I was also working on the soil substitute in the background.

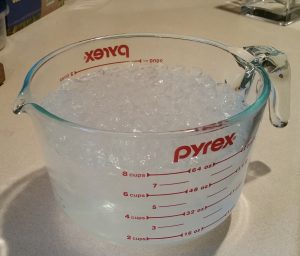

It comes as a little bag of gelatin grains, and they need a few hours to expand. 10 g of grains is about a teaspoon, and is enough to make half a gallon of soil substitute, according to the package directions. So I measured out my particles, added water, and left them to sit. Within about 30 minutes, they looked like this:

A few hours later, they looked a little like ice cubes and felt like very firm Jello.

When I first put them into the container, they didn’t look very transparent at all. That’s because there were a lot of air gaps between the gelatin particles, which refract light.

Submerging them in water helped quite a bit, but it was still a bit hard to see through the container.

Repeated pressing and squeezing got rid of the larger air bubbles, and the gel was starting to look a lot more clear.

Unfortunately, those air gaps are important for the plant, whose roots need to breathe. Flooding the gel with water will make it nice and clear, but long-term it can also drown the plant. I’ll need to do that for a few hours at the exhibition, but until then I’ll stick to a more plant-centered approach. So, I drained the gelatin again, in preparation for potting.

Once the soil medium was set up, I did a little more surgery to remove the second sprouted branch from the tree. I pushed the stem down into the gelatin, and wrapped the container in aluminum foil to reduce light penetration. After defoliating the branch a bit, I let it be.

I also took advantage of the unseasonably warm weather to take a few soil samples from my garden for the freezer. I discovered during my soil autopsy last January that thawing soil is the smell of spring (somehow I seem to end up doing a lot of things with soil in January…). There’s no guarantee that the ground will be thawed enough to collect samples in March/April, and I suspect that most of the scent is released in the first gasp of life after the first thaw, so I took 4 samples of hibernating soil, saved them in ziploc bags, and put them in the freezer to preserve a dose of spring air for the exhibition. A little Googling led me to coffee bags with one-way valves (used to release CO2 from freshly roasted beans, also used by consumers to smell coffee in the coffee aisle), and I’ve ordered a few with a transparent backing, so that people can both see and smell spring.