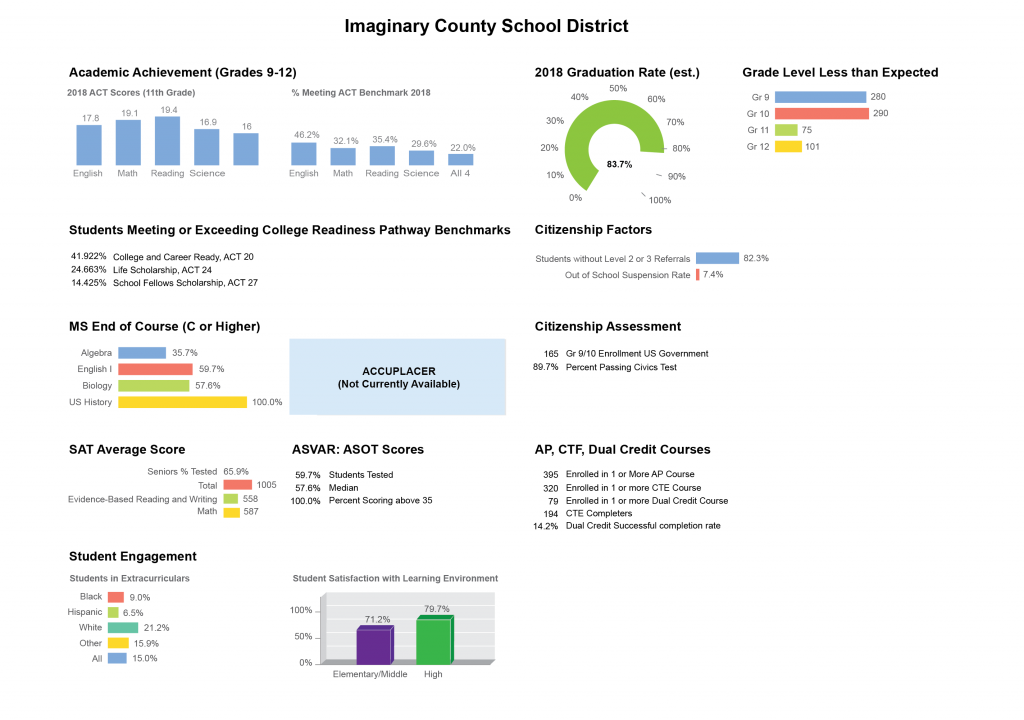

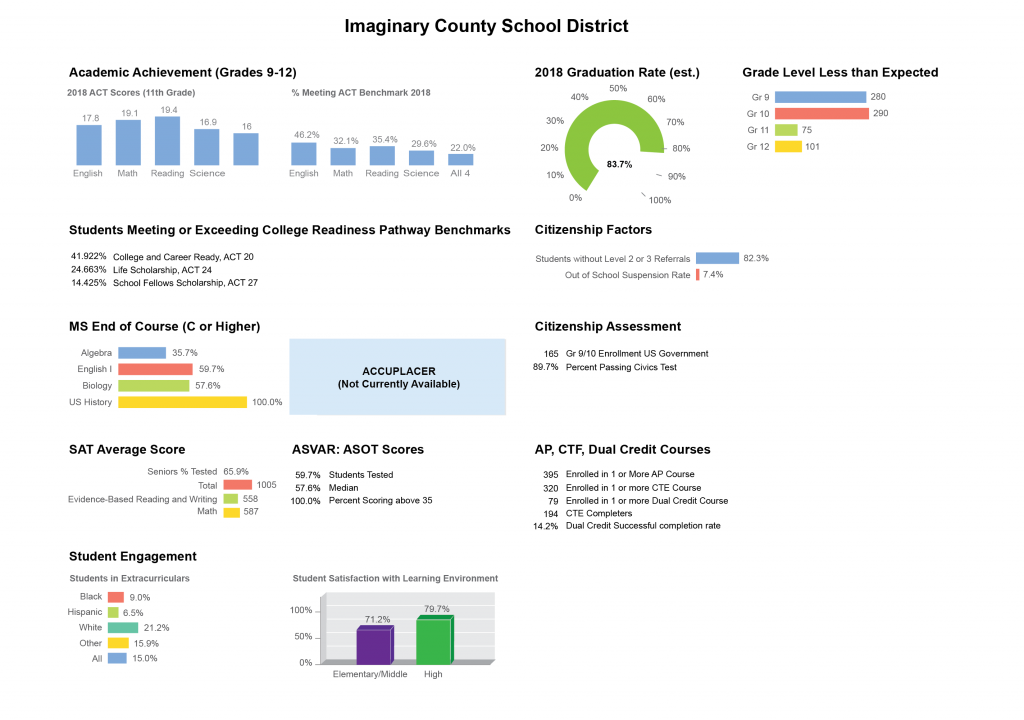

This article is part of a series that illustrates how basic design principles can improve information display. In the last installment, we thought through the purpose and context for a dashboard that we are redesigning. Up next, we will dive into revamping the content. Before we do that, it’s good to take a moment to pause and look closely at the original chart choices, to get a sense of what is (and isn’t) working well. We laid out some good, basic considerations for optimizing the styling details of chart displays in a previous post, so here we’ll focus more on applying those recommendations in context, and commenting on the charts that are already here.

The designer of this dashboard has stuck mostly with bar charts, which are usually a safe choice. Bar charts are familiar to most people, have high quantitative accuracy, and can support users in comparing values and proportions. In general, this is a good choice. Bar charts are also amenable to annotations and various other “upgrades” that can help when we want to add more comparisons into the charts, so they can be quite flexible. The last article discussed several pieces of additional information that a user might need to make sense of this data. It remains to be seen whether simple bar charts will still be the best choice when we think through all of that information and the tasks it implies, but for right now, bar charts make sense.

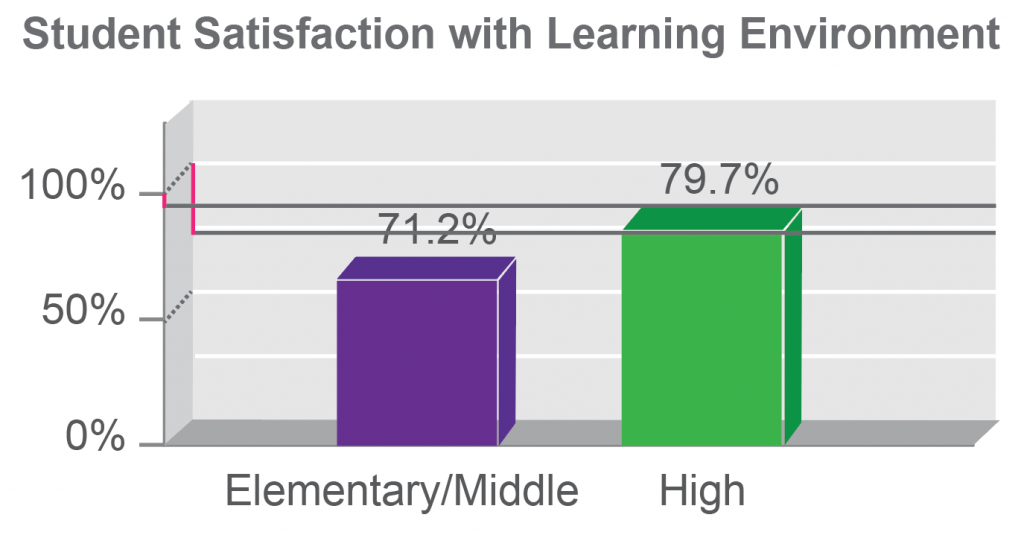

Probably because bar charts are familiar, reliable, and safe, they are often dismissed as boring. It is one of the great myths of dashboard design that if you just “jazz up” your dashboard a bit by picking fancier charts, people will automatically want to spend more time there, looking at things. In my opinion, that’s a lot to expect from an individual chart choice, but we’ll leave that discussion for another day. For now, we’ll focus on the things that, to me, are more successful in improving user engagement, because they make the dashboard itself more useful. We talked about content in the last article. Today, we’ll focus more on clarity and function. I only mention the “boring” factor here because I suspect that’s what led to the more questionable charting choices in this display. If you’re just trying to make a bar chart more exciting, you could try making it 3D.

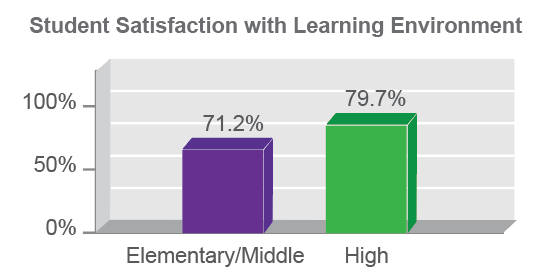

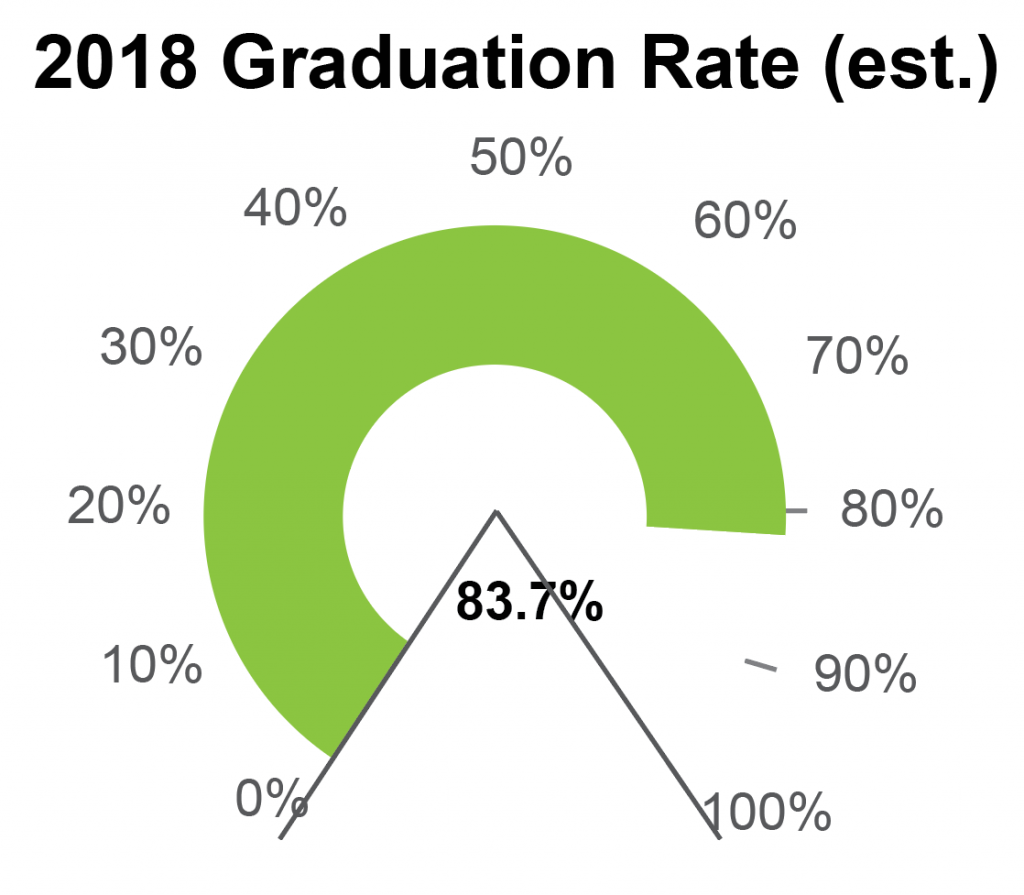

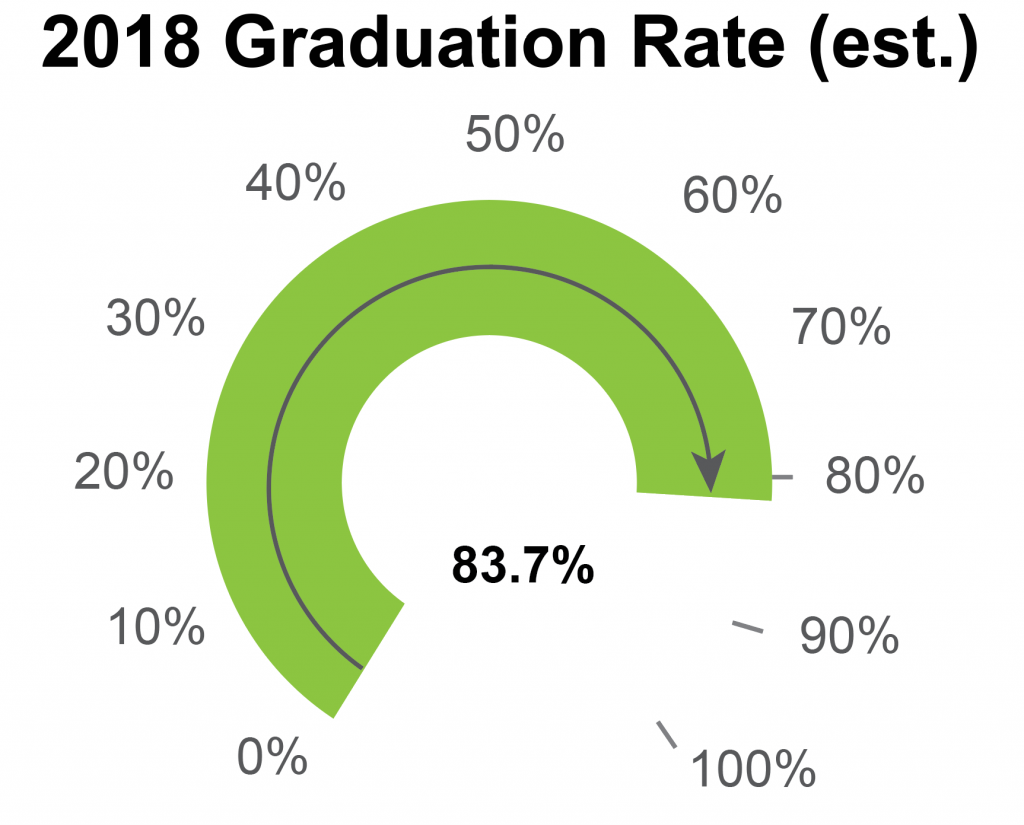

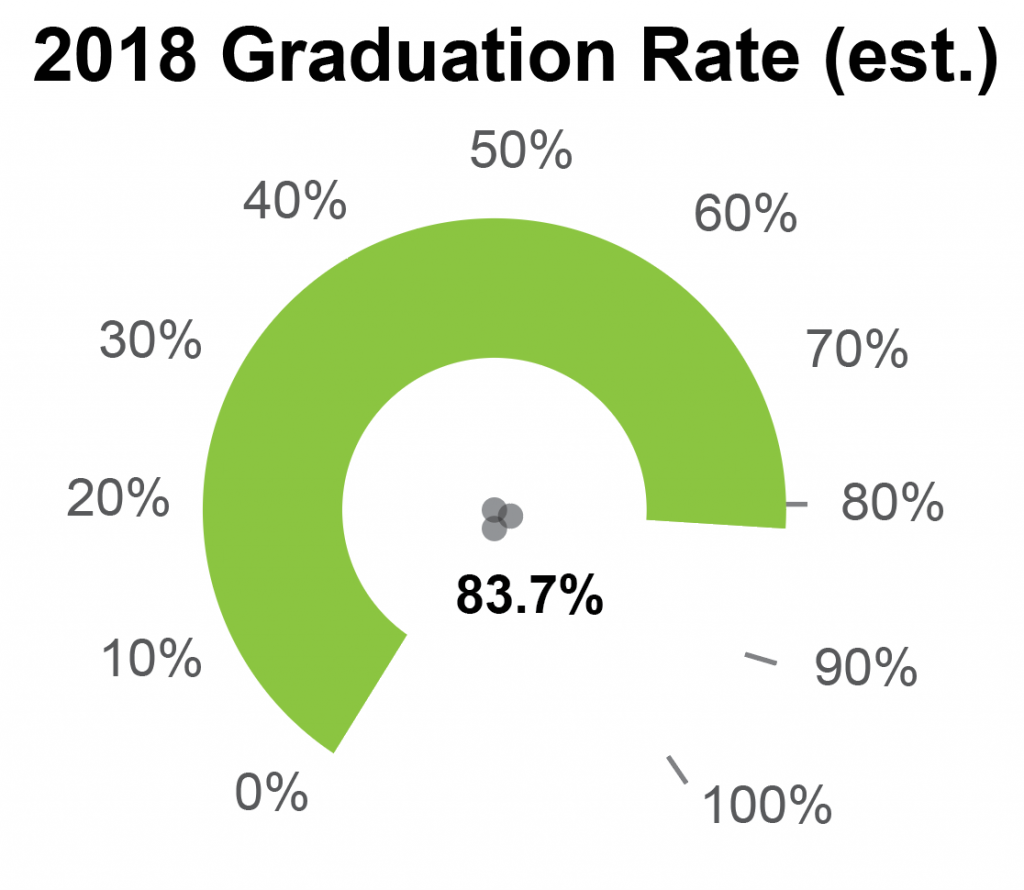

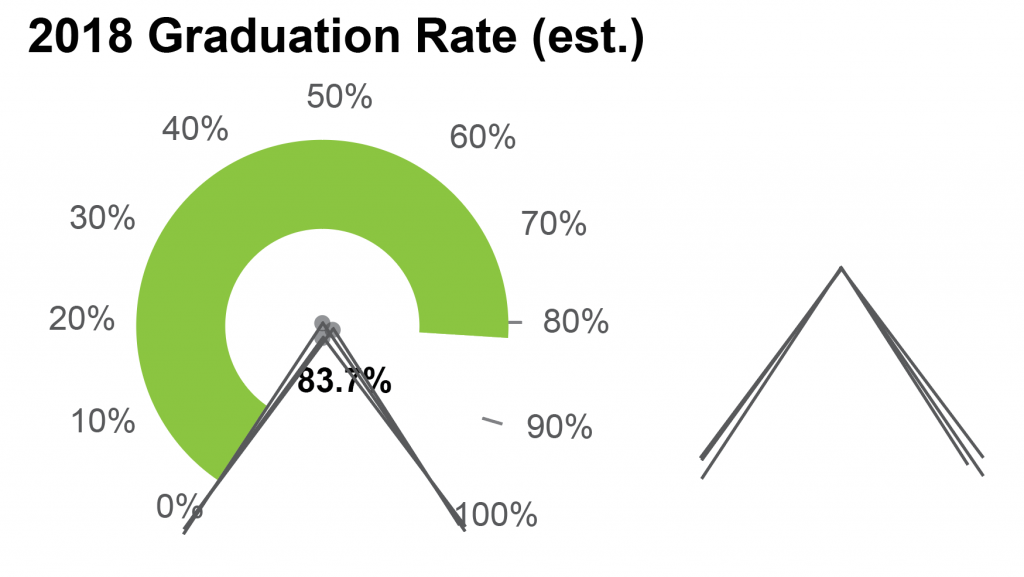

Or, you could try bending it around a curve, to look like a speedometer in a racing car. (Nothing says “exciting” like a speedometer display, with its implicit message to “go faster!”)

Neither of these choices is criminal, but I am skeptical that they are really improving the display. Both charts make the data harder to read, and they don’t add extra information that the user might find helpful. The 3D chart, in particular, feels kind of random and out of place, because it’s the only one like it on the page. The speedometer display does at least have the advantage of a more compact aspect ratio, and it is debatable whether the data would be better served by a single, long bar. The dashboard designer has done a good job of labeling values to offset the difficulties inherent in reading these different charts, so I would say that these visualizations are not really doing any harm, but I don’t think that they are helping, either. Let’s take a closer look at some of the difficulties that these charts introduce.

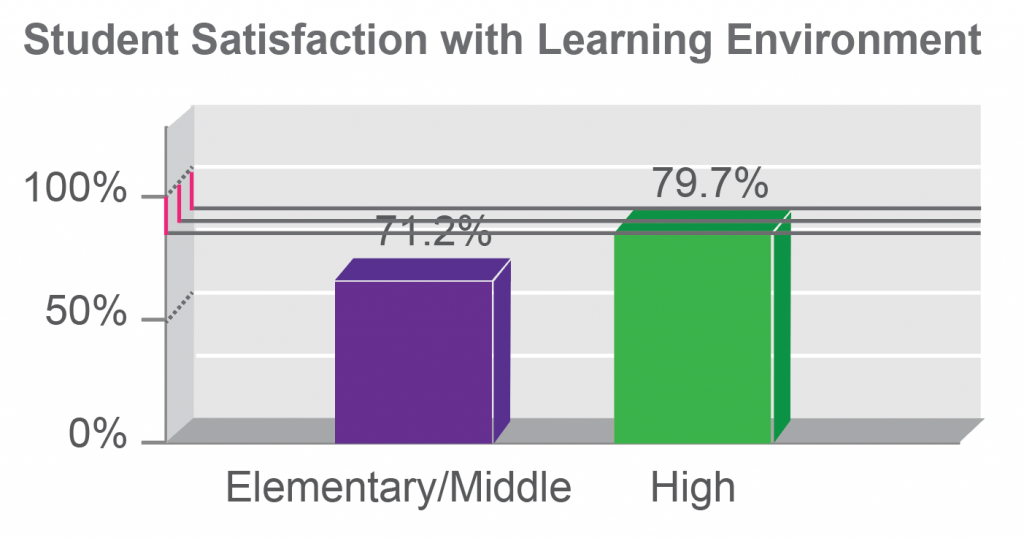

3D charts are easy to pick on, because they introduce cues that can fool our perceptual system into misreading the chart. Unlike some hard liners, I do think that there are some contexts where the use of 3D visualization is justified. When introduced carefully and with the proper constraints (and for users who understand how to read and use a more sophisticated chart, along with controls to help them interpret it), that third dimension can sometimes provide an additional comparison that is difficult to achieve in any other way. This is not one of those cases. Here, the 3D aspect is simply a catchy style element: it doesn’t add anything new to the contents or comparisons in the chart. And, it makes it harder for a user to see how the bars line up with the axis. To help illustrate this, I’ve added three thick gray lines to the top of the taller bar: one at the front, one in the middle, and one in the back. Any one of these could be reasonable anchor points for trying to read values off of the chart.

The way the axis labels are drawn, the new gray lines help us to see that it is the front face of the bar that we should use to read values, because that’s the one that intersects the labeled axis. To read the chart, the user needs to complete the task of determining the distance of this intersection from the labeled values, which I’ve highlighted with a magenta bar. Notice that the user also needs to add an imaginary line, drawn here as a dotted line, connecting the labeled tick marks to the back panel of the chart to make comparisons for the second and third solid lines. Depending on which solid gray line the user chooses as a reference, the magenta difference will need to be measured at different points along the dotted gray line. As long as the user gets all those imaginary lines lined up right and accurately judges their intersection and the resulting lengths, there is no problem: all three magenta lines are the same, and the user will be able to read this 3D chart. The problem is that most people won’t be able to accurately judge that intersection. It is just a much harder task than doing the same comparison in 2D, and it’s one where your own vision system works against you.

So, what if the user gets it wrong? How much difference will it make, really? Quite a lot, in fact. In this second version, I’ve simply extended the solid gray bars to hit the axis plane at different points. I’ve swapped the drawing so that the line from the front of the bar hits the axis in the back, and vice versa. The front line hits the back axis just below the 75% gridline, while the back line hits the front axis at just below 100%. Assuming that there are no other sources of error from the 3D display, simply adding in these errors from mis-applying the 3D projection could make a difference of almost a quarter of the value represented in the chart. To me, that’s a pretty big deal, and the 3D is simply not giving us enough to make it a worthwhile tradeoff.

Notice how much one small design decision could improve this chart, if your job was simply to make it better. Instead of putting the charts in a shadow box and reading off the front of the chart, what if the designer had chosen to put the tick marks on the back panel, and read off the back of the bars?

Notice how much simpler that one adjustment makes things. It reduces the sense that the chart is 3D, but it becomes much easier to read once the axis lines actually match the gridlines drawn in the chart. This is a good reminder that we always have design decisions to make, and that even small things can make a huge difference in the usability of a particular chart. Understanding why something is broken always makes it easier to fix.

The user will also encounter different difficulties when reading the speedometer plot. Here, there is no 3D representation to throw off our perception, but the reference points are a lot harder to read than in a standard bar chart. Notice that the graph starts at zero and ends at 100%, but it doesn’t use the full size of the circle. It also doesn’t look like quite three-quarters of a circle, either, so it’s probably some arbitrary value set based on how the final chart looks. My guess is that this is done for aesthetic reasons, and to allow the chart to accept values over 100%. Adding in some guide lines helps to make that a little bit clearer.

Without getting out a protractor, I’d guess that the angle between those end lines is about 60 degrees, so the chart arc spans about 300 degrees, or about 83% of the total value. It’s an interesting coincidence that that’s almost exactly the same value that’s shown in the chart, but the two should be unrelated – unless someone made a mistake in the math somewhere when scaling the chart. For now, we’ll assume that the initial graph is correct, and that this is just a coincidence.

By not using the whole circle, the chart introduces a discrepancy in scaling, which the user will have to overcome when estimating values. The arc drawn here is drawn as about 60% of a circle but represents 80% of the total measurement of 100%. Confused yet? The chart designer has thoughtfully helped us out by adding ticks for those last few values, which makes it a lot easier to read the value where the green bar stops. But the bar will still hit 100% before the arc makes 100% of a circle, which makes the visual impression a little misleading. If I just glance at the chart, I read this as just over half a circle, but it’s actually more than three quarters of the way to 100%.

Technically, the speedometer is actually a distorted bar chart, and its values should be read as a lengths rather than angles, but I don’t know of any good way to estimate arc length reliably with my eye, and always revert back to comparing the ratio of angles for the bar to the chart max to estimate the value for charts like this (green bar is at 250 degrees, 100% tick is at 300 degrees, which implies a ratio of .8). There’s a lot of estimation and math in my head involved there, which increases my difficulty when reading the chart, and decreases the accuracy of the values that I guess.

It’s also interesting to notice what I had to do when I wanted to accurately guess the angle values: I had to find the center of the white circle in the center of the graph. What I’m really doing in this case is trying to put an imaginary line on each flat end of the green bar, and then figure out where they intersect. All the other noise in the chart (and especially that center label) make it much harder for me to guess the center precisely.

And again, we might ask ourselves: how much difference does it make? How much uncertainty is the unmarked center really likely to add to this graph? Fortunately, it’s pretty easy to tell. By drawing my imaginary reference lines from each of the different centers to the 100% tick and the point on the arc closest to the zero value, I can see how much variation there is from misplacing the center. By laying these three pairs of lines on top of each other, I’d guess that there’s a variation of maybe 5 degrees. Not as severe as last time, perhaps, but significant nonetheless. Remembering that our user is trying to eyeball this from a small chart in a noisy dashboard, you can see that eliminating this point of reference could very easily lead to mistakes.

Fortunately, our thoughtful dashboard designer has at least partially addressed concerns for both charts by including labels so that the user doesn’t need to read directly off the chart. This goes a long way toward answering the most urgent accuracy concerns, but it should leave us wondering: why show the chart at all? Visualizations are complicated to make and can be expensive to produce, and I think we should always insist that they pull their weight. What is the visual doing for us, if it’s likely to distort the user’s perception and add inaccuracy to the data? The answer here seems to be mostly adding visual appeal, and increasing the visual weight on the page. But it would be far better to include a visually appealing chart that does not appear to contradict the numbers that you’re supposed to see. When you get to the point where the chart is just window dressing, I think we should also ask ourselves whether the visualization could be doing more, or whether it should be removed altogether. That’s a question that we’ll return to in a later installment, when we get to the full redesign. For now, let’s go back and take a look at the dashboard as a whole.

When I just glance at the dashboard, I see vertical bar charts that are displayed side by side, which supports the user in comparing bars from one chart to another. It looks like the axes are aligned, which is good; we wouldn’t want them to be offset if we are comparing values between charts. But notice that the axis scales are not the same: one is in points, and the other is in percentages. So we shouldn’t really compare values between these two charts after all. That’s fine, but the way that these two charts are grouped together, the fact that they are the only vertical bars on the page, and the fact that they are the only charts on the page where all of the bars are blue all reinforce my assumption that I should compare between them. There’s nothing wrong with how this is done, per se, but we should be aware that users will be looking at subtle cues in the visual design to understand how to group things together, and we want to make sure that the relationships are as clear as possible, and that we’re not implying groupings that don’t exist. I also notice that the vertical bar charts have been squeezed vertically to take up less space, which makes differences in the data harder to see.

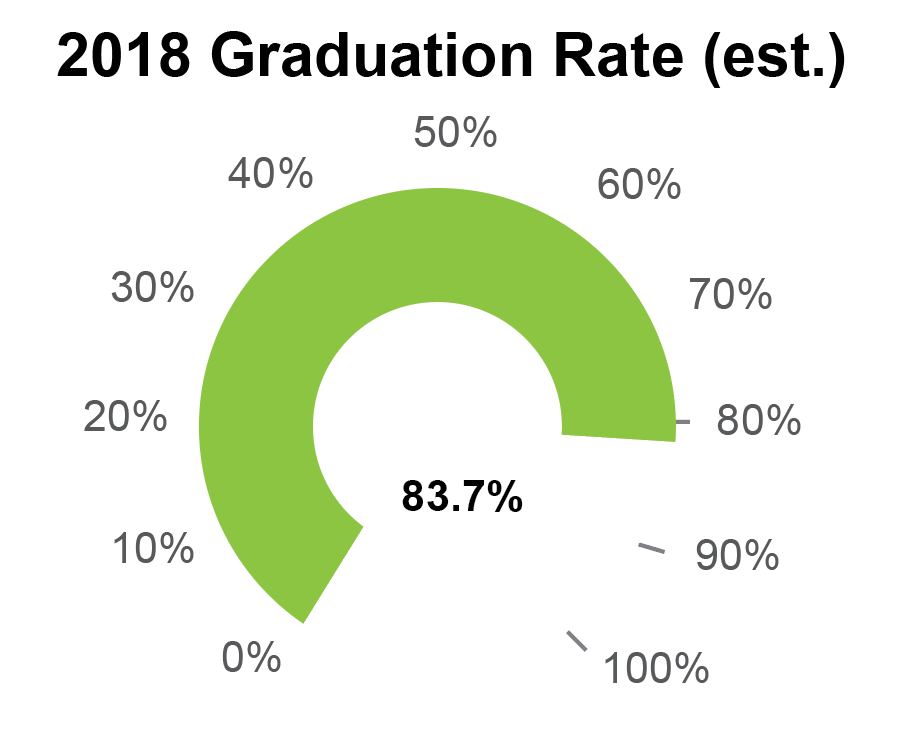

Another thing I notice right away is the use of color. The colors are quite strong, but their application seems to be arbitrary. Red does not mean “English” in every chart. There does seem to be a rule that says that the color order should be blue, red, light green, and then yellow, but that order is violated in the Student Engagement and Student Satisfaction charts, and it’s not immediately clear why. It is common to re-use colors from chart to chart, so I wouldn’t think much of it if the order was always the same, but it feels intentional that the order was broken in the Student Engagement chart, especially since a new color was introduced right in the middle of the standard sequence. The only other place that this particular green shows up in the display is in the second Student Satisfaction bar, but there does not seem to be any reason for linking those data points. It’s also interesting that the purple used in the Student Satisfaction chart does not show up anywhere else, or match any of the other colors in the dashboard, which makes the green grouping seem more significant. The fact that the Student Satisfaction chart is styled so differently than the rest of the charts makes it seem less related to the other information – or possibly more important.

It’s good to keep in mind that color is a strong grouping indicator for most people, and even if you don’t intend to create relationships, people are likely to seek them out. Having a simple, clear order helps to reduce that tendency, because users can easily check whether there is a relationship. Once an order is established, people will start to look for and try to create explanations if you break it. Having a color code that “sometimes” holds is often more confusing than not having one at all. This is a huge headache for dashboard design, because colors are often assigned automatically when the data changes, and it’s very hard to control what the user will actually see on a given day. There are no easy answers to this conundrum, but it’s good to remember that color is one of the most powerful grouping tools you can have, and you want to think carefully about how to use it well.

It’s also interesting that the designer chose to mix vertical and horizontal bars. I suspect that this was due to label length and vertical space considerations, but I’m not 100% sure. It may also have been an attempt at visual variety. Both bar chart versions work, and I don’t know of any rules that govern mixing them, but it’s good to remember that it will always be easier to compare vertical to vertical and horizontal to horizontal charts, and that our brains tend to assume that visually-similar items are related. If that’s not what you’re going for, then you might want to introduce other cues that weaken those perceived relationships (position charts differently on the page, reinforce alternate groupings, use different colors for bars in chart 1 and chart 2, make titles more prominent, etc.). Amer and Ravindran published an article in 2010 explaining how a common optical illusion can distort length comparisons between different orientations of bar charts. Including labels and gridlines is a simple fix, but it’s an interesting result that’s worth considering when building a dashboard where a user might need to compare between charts.

These are just a few of the first things that I notice as I start looking at a dashboard. Really, I’m just paying close attention to what I see, the connections I’m making, and whether or not those assumptions turn out to be correct when I examine the data more closely. I’m paying attention to what puzzles me, and where I might be making mistakes. It’s good to examine these different strengths and weaknesses before we begin thinking about how to re-design the dashboard. There are lots of other factors that will come in as we add more layers of information, but it’s good to have a basic sense of where you’re starting from before diving in. In the next article, we’re going to take a brief detour to think about chart choices and how those relate to user tasks, to inform how we compare the different chart options when we start to redesign.

To sum up, here are a few of the questions that I’m asking myself as I start to look at a dashboard for the first time:

- What do I see first? What’s most prominent on the page?

- What do I notice at a quick glance, vs. on a deeper look?

- What kinds of connections am I making between different charts? Do those assumptions seem to match the designer’s intent? Are the visual cues I’m picking up on intentional clues left to help me out, or random artifacts left by unexamined design choices?

- As I start to read the content more closely, when am I surprised? What mistakes did I make when I first glanced at the page, and why? (Note that I don’t believe that every mistake can or should be prevented, but it’s helpful to pay attention to what they are and when they occur, because that helps to inform the design.)

- When do I want to reach for a ruler as I’m reading a chart? Are there places where I just can’t tell what’s going on? What kind of annotations or guidelines would help me out there?

- Why do I think the designer made these choices? Is there something that they were trying to do here, and was it successful? Is there a better way?

- How does the dashboard feel as I’m reading it? Is it structured and logical, or jumbled and confused? Can I tell right away what’s going on?

- Do the chart choices make sense for the kind of data that they’re showing, and for the kind of task I need to do? Are they supporting me in reading the data, or are they getting in the way? Are there better options, or additional things that I want or need?

- What kind of annotations, interactions, or other information could help me out?

1 thought on “Dashboard Redesign - A Look at Chart Choices”